“It seems you’re lucky that I sat next to you,” she said as she took off her fox fur cap and settled her large body among the sea of Armenians occupying the flight from Moscow to Yerevan. The plane was mono-ethnic, full of men and women whose expressive faces were carved and etched with line after line of stories and experiences from times and places known only to residents of the Caucasus. Men who were coming to spend a few months in Armenia after earning wages to sustain their families, women who were visiting their daughters, studying at universities only three hours away by plane, but still too many kilometers away as far as they were concerned.

Her name was Lusiné. She asked me where I was from in Yerevan, but as soon as I opened my mouth to answer, my melodic accent gave way to the fact that I was a foreigner headed to a homeland.

“It’s my first time in Armenia,” I blurted out with a smile. It was immediately after that I got my first taste of the Armenian hospitality so widely spoken of. She didn’t say anything, just reached over, grabbed my face and gave me a kiss as if she was my own grandmother.

She explained that her family, like mine, was originally from Iran, that she had come to Armenia at a very young age, but was proud from the country she descended from. She pointed out her jewelry, a ruby encrusted ring that dangled from pink nails that must have washed a thousand plates, a gold chain link bracelet, both of Iranian origin.

She asked me why I was going to Armenia, then invited me over for dinner. Then she told me about her 13 grandchildren, and how my stay was too incredibly short to get anything worthwhile out of the trip. She recounted all of her children’s names, where they lived and what they did. She told me to make sure I call my parents when I land. They would be worried, you know. She lamented about relatives she hadn’t seen for eons who lived in Los Angeles. If she told me all their names, she was absolutely sure I would know who they are.

The Nutcracker suite played over head while a young stewardess named Viktoria demonstrated emergency procedures should there be trouble, as the hungry eyes of Armenian men who were shuffling cigarettes gravitated towards her like magnets. Lusine caught me writing in my notebook, and there, squished in between the ice cold window and her pink crocheted poncho, I had committed my first sin: I was a lefty.

“That’s not good!” she said. “Didn’t they teach you to write with the correct hand?”

It was there that the tone of my trip would be set – Armenia, a land of charm, melancholy, endearment and contradictions. A place that boasts a capital city 29 years older than Rome, where ancient churches proudly stand among the descendants of their erectors, where women sweep the streets with brooms that look like decorative wall pieces found in Western kitchens, where yellow Soviet area gas stations stand empty, with only electric pink mini Christmas trees to keep them company. A place with food so good, you feel like you’re tasting the Earth with every bite, where emotions, life and realities overwhelm you with swift punches in the gut. A place where you’re made aware of the triviality of your regular life almost immediately, where superstitions and misconceptions about what you most probably take for granted run side by side stark with economic hardships of a people who have been plagued by wars and conquerors, earthquakes and genocides – and still somehow managed to survive.

Yes, survival, a word that is synonymous with Armenia for the people and street dogs of this little landlocked country that many haven’t heard of and most will never visit. What does it have to offer, this Armenia? This rugged Armenia that is ripe for change and revolution, where underground night clubs translate into a world of social and sexual freedom and lovers kiss in between the bushes that caress an architectural feat of a modern art museum. This Armenia that’s magical, that allows voices that normally would be drowned out in a crowd to be heard loud and clear, for better or worse.

This Armenia has changed me. It has penetrated my being in ways which words surrender to – expressed in chills and tears.

“Coming to Armenia is only hard the first time,” someone said to me. “Every trip after that becomes infinitely easier.”

This is what Armenia does to you. It grabs you, regardless of ethnicity. It grows in you, pumping with the blood in your veins and digesting the food you eat. It causes you pain so you can appreciate its pleasure and never lets go.

The thing about the first time in Armenia, is that it is an unwritten rule, in your passport or otherwise, that you will return again. In six months, in 20 years, with family, friends or alone, you will return again, because the magnetic field of Armenia is hard to resist, it pulls you back in as soon as you leave.

When the plane landed, I had adopted Lusiné as my own, as she had done me. I waited for her to gather her belongings and put her hat back on. We walked down the connector and into the airport together at 4 a.m. Somewhere along the shuffle of luggage and passports and lines, I lost her. Or she lost me. She had planned on giving me her information, but we never got to that.

“Next time you’re here, you’ll come over and I’ll make you dinner,” she had said to me. Numbers were never exchanged and Lusine vanished from the airport to her home a few miles outside Yerevan.

But you know, I have a funny feeling I’ll be seeing her and Armenia again. The universe demands it.

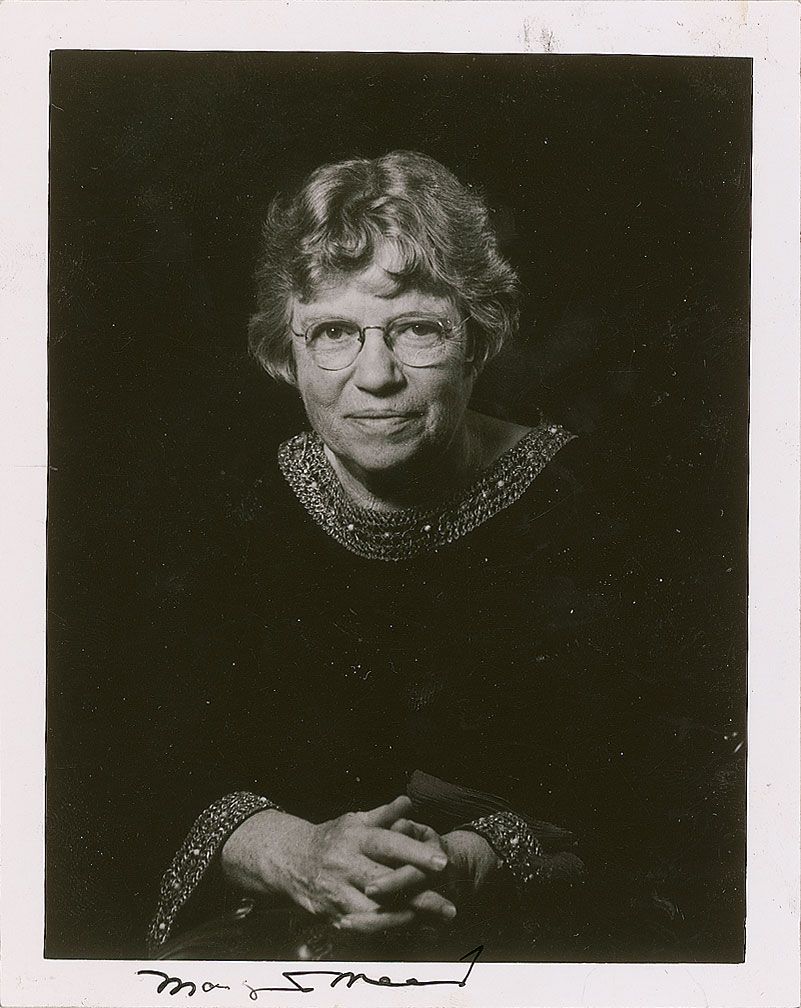

Liana Aghajanian

IANYAN mag

An independent Armenian publication